|

|

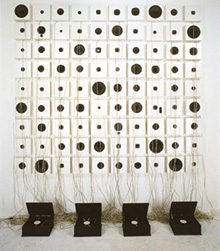

| Nadine Robinson Conclusion Of The System Of Things November 4 - December 17, 2005 Christine Y. Kim The End The Bible's Book of Revelations, the final book of the New Testament, offers an ominous, menacing picture of the future. It begins with John's prophesy of the second coming of the Lord. Emerging ethereally from the clouds, he announces "I am the Alpha and the Omega, who is, and who was, and who is to come, the Almighty." (Revelations 1:8) Dressed in a flowing, white robe tied with a gold sash, topped by locks of white hair, "the whiteness of wool, like snow, his eyes like a burning flame," (1:13) he holds in his right hand seven golden stars for the seven churches of Asia. The chapters that follow describe the separation of the saved from the damned. According to John, in the end, 144,000 people (12,000 people from each of the twelve tribes of Israel) are saved. They are reconciled with God in the Holy City, the Kingdom of Heaven, the New Jerusalem, to drink from the water of life, forever wedded to God, while Satan's followers are "tormented day and night for ever and ever." (19:10) Whether ranted on a New York City subway platform by a self-proclaimed prophet, sermonized at mass by a Catholic priest, or read silently to oneself, the foretelling of doom in the Book of Revelations is an emphatic, threatening story of the end of time. The devastation of the earth is commanded by seven angels who appear before God. The third angel is granted the great Wormwood star, which appears as part of the opening of the Seventh Seal, to use for destruction.1 When the third angel sounds his trumpet, "a great star, blazing like a torch [Wormwood] fell from the sky on a third of the rivers and on the springs of water… a third of the waters turned bitter, and many people died from the waters that had become bitter." (Revelations 8:10-11) Nadine Robinson mines religious doctrines and prophecies of doom, specific to these passages from the Book of Revelations, as material for her most recent body of work. While the large-scale sculptural installations appear as minimal forms, they are informed by a vast range of references, including fairy tales, Rastafarianism and Hollywood films. In the end, myriad images, objects and sounds manifest as a foreboding yet whimsical statement of globalization and civilization as we know it. They offer complex hypotheses and propositions as art. Robinson's sculpture, Wormwood, takes its title from the third angel's great star of destruction in the Book of Revelations. With a diameter of eleven feet, over 500 lightbulbs fill this seven-pointed star. 13,000 watts are emitted, blasting the viewer with extraordinary heat and light, blazing like a torch, as in the bible, wreaking havoc in the form of poisoned waters and floods. "The bitterness of wormwood, gall, and the symbolic Wormwood Star," explains Robinson, "echoes the harsh times in which we live." She cites American war machines poised throughout the East (Middle, Far, Near and South), the development of nuclear arms and the ongoing war in Iraq. She also lists AIDS, famine and earthquakes on the list of "the spector of Revelations… how it looms in the popular imagination today, reinforced after the horror and spectacle of September 11th and Hurricane Katrina." On one hand, Robinson's new work represents a radical departure from her previous works of art, namely the portraits. Laquita (2004), a portrait of a childhood classmate, is an enormous crest-shaped black canvas covered in braided human hair used for weaves and extensions. Self-Portrait #2 (Boomtoon) (2001), a "boom-painting" self-portrait, consists of one black panel embedded with speakers in the form of a face. The soundtrack repeats songs, such as the doo-wop track, "Nadine" (c. 1955) by Allan Freed, performed by the Dells; "Nadine" (c. 1950) by the Coronets; and "I love Nadine" (1959) by the Love Tones. These literal depictions and playful forms recall practices and icons of Black culture and Americana. On the other hand, however, Robinson's new work is a dramatic extension of her artistic practice, namely through her use of soundtracks and dubs.2 For many Christians, whether backed by choirs lamenting Gregorian chants or triumphant trumpets reminiscent of the "loud voice of the Spirit" (Revelations 1:10), the end is imagined accompanied by dramatic music. Robinson's new work, Alles Grau in Grau Malen (2005), offers a soundtrack for the end of time. It is a large-scale sound painting measuring over eleven by forty-five feet. Fit onto one wall, it is accompanied by fog emitted from low-lying fog machines, obscuring the rigor of the white cube. The built-in audio player components play a mix of popular dramatic soundtracks taken from Hollywood films and Jamaican dance music. The pounding and chanting tracks derive from the climax scenes in Rosemary's Baby (1968), The Omen (1976) and The Matrix (1999). These manufactured movie versions of synchopathic sounds are mixed with Catholic funerary chants. Special effects specific to Jamaican sound systems are then piled on, in the tradition of Houses of Joy3 . According to Robinson, Jamaican culture is inextricably bound to the Book of Revelations. Rastafarians believe that they are descendants of the tribe of Benjamin and will be saved at the end of time.4 Echo effects and air horns, most commonly found in Jamaican dance music are reinterpreted as a kind of "doom dub" in this work. Each of these tracks derives from a different vernacular for the end of time. Although they are more intensely abstracted, Robinson continues to infuse personal narratives in her new work. The dense fog represents both the clouds upon which the Lord God appears in Revelations, as well as one of Robinson's early childhood experiences in Jamaica, when she was lost in her father's gungo-pea "poor man's plantation" outside of Spice Grove. Robinson was found days later covered in cuts and bruises, dehydrated and delirious with the fear of death, as seen in the jancrow flying overhead. "This is the place," describes Robinson, "that my father explained as the home of ghosts." Her petrified family thought the ghosts had claimed her life. These beliefs, also hybrids of Jamaican Obeah and Santeria, which, according to Robinson, is a sort of "Africanized Catholicism," echo transcultural variations on the end of time. In addition to these cultural and personal narratives, Robinson consistently layers in references to Western art history. She cites, for example, her primary artistic influences - Ad Reinhardt and Robert Ryman - when discussing the Modernist underpinnings of her work. (Robinson often speaks of "The Three Rs:" Reinhardt, Ryman and Robinson.) The tug-of-war between minimalist aesthetics and vernacular semiotics is also present in Alles Grau in Grau Malen, specifically in the notion of 'paintings with sound,' or 'paintings that can speak.' Robinson's sound paintings question if language can be abstract, minimal or non-objective, and therefore challenge essential discourses of Modernism. Formally, the hundreds of speakers embedded in Alles Grau in Grau Malen reflect the figural arrangement of Michelangelo's fresco, The Last Judgment (c. 1536-41) painted in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican in Rome. Considered Michelangelo's most controversial work, pessimism and emotional turmoil dominate the altar wall. Focusing on a horizontal band of Christ in judgment, Robinson's undulating speakers mimic the saints' bodies, twisting and turning. In Alles Grau in Grau Malen, which in German means "to paint everything grey and black, or pessimistically," the sounds, sights, and sensations are pointed and powerful. Robinson believes, "vision encourages projection into the world, occupation and control of the experience. Sound encourages a sense of the world as received, as being revelationary rather than incarnate."5 In this mode, Robinson's sound paintings attempt to reconcile conflicting canons of Modern painting and Gothic art. Or, perhaps in reverse chronological order, Robinson attempts to undo or reverse time through the history of painting: to turn the end into the beginning, and the beginning into the end. From ancient times to the twenty-first century, religious groups and individuals have prophesized the coming of the Lord through natural catastrophes and disasters. This season, Hurricane Katrina, which devastated the city of New Orleans and took over a thousand lives, has been seen by some as a sign of the end of time, or, more specifically, as a manifestation of angels' paths of destruction from the Book of Revelations. Religious organizations and individuals, zealots and fanatics claim to have found symbols and signs pointing to Biblical prophecies. One pro-life group went as far as to read the outline of a fetus in the shape of Hurricane Katrina, right down to the eye.6 But this is not the first such instance of apocalyptic predictions. The 2004 tsunami in Southeast Asia, which followed rains, floods, typhoons and monsoons in Haiti, the Domincan Republic, the Philippines, China and India the same year, claimed hundreds of thousands of lives.7 Whether Christian, Muslim, agnostic or atheist, it might be difficult to avoid questions like: Could the end be near? Or, is the end really just the beginning? Is Revelations actually the Book of Genesis? The Beginning

1 This mention of Wormwood is the second in the Bible. Also the name of a bitter herb used in the manufacture of "abysinthe," a hallucinogenic liquor, it is first mentioned in the Old Testament: "Therefore thus saith the Lord of Hosts, because they have forsaken my law, Behold, I will feed them, even these people (Israel), with Wormwood, and give them water of gall to drink. (Jeremiah 9:13-15) 2 Tower Hollers (2001) was actually the first sound painting in which Robinson created choral and orchestral sounds. The mixes on vinyl consisted of easy-listening "muzak" and work songs from slavery such as, "Go down, Old Hannah, Don't ya Rise 'till Judgment Day," amplified through 100 speakers. 3 Houses of Joy is a colloquial expression/term used to describe large sound systems composed of an amalgamation of stacked speakers. These systems are popular in public spaces in urban areas of Jamaica. 4 Haile Selassie (1892-1975), descendent of King Solomon and Queen Sheba, is regarded as the Messiah of the African race by followers of the Rastafarian movement. The word "Rastafarian" comes from Selassie's pre-coronation name, Ras Tafari. 5 John Shepard, "Music as Cultural Text," in The Routledge Companion to Music (London: Rougledge, 1993) 148. 6 Klein, Joe, "Listen to What Katrina Is Saying," Time Online Edition, September 4, 2005, (October 5, 2005). 7 The government of mainland China in Beijing does not disclose the numbers of victims of natural disasters, thus many disasters that took place in China may not be known to the rest of the world, and estimates are conservative.

|