|

|

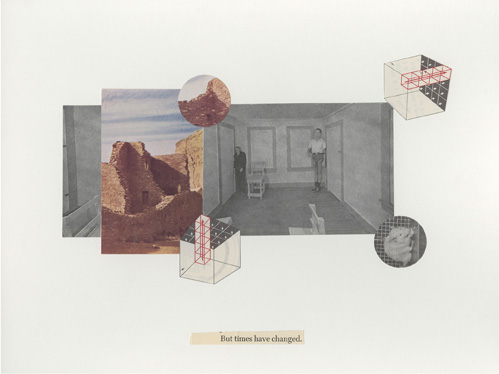

The Juvenal Players: Five people sit on a discussion panel in a gallery surrounded by works of art. They have gathered posthumously to celebrate Juvenal Merst’s art legacy, at his request, seven years after his tragic death. The discussion is supposed to precede the reading of a mysterious, sealed letter written by Juvenal, followed by the presentation of a performance, Merst’s last artwork. The speakers are Juvenal’s closest friends and acquaintances. The moderator is Clifford Barnes, an art critic and writer who had been a scholar until he was fired from a university. The other participants are: Miranda Saks, a young, former artist who used to have a close relationship with Juvenal, and now works making cheese at a farm in upstate New York; Rosaura Valparaíso, head of the Rosaura Valparaíso Foundation, a collector and widow, who owns several of Juvenal’s pieces; Sonja Stillman, a scholar engaged in social issues and curator of the Southport University Museum of Contemporary Art in Sabbathday Lake, Maine; and finally, Elmer Schafroth, another former artist who collaborated for a time with Merst and has become the Associate Manager of the Clybourn Arts Studio, a not-for-profit arts organization in Chicago. Merst’s real name was Joshua Emmanuael Merst, but he changed it to Juvenal in honor of the Roman poet and sharp satirist. Barnes introduces him as a respected, controversial and extremely provocative conceptual artist, an “artist’s artist” who produced a small body of work (“the most compact oeuvre of any major artist in the last decades”) before his untimely death. The conversation turns sour quickly and civility evaporates right after the presentation. Tensions and grudges appear among the panelists and shatter the solemnity of the event, turning the celebration into a volatile confrontation. Juvenal becomes the pretext for venting anger from old disputes, rejections and gossip, from clashing antagonistic views of art. The event doesn’t turn into a “love-fest,” as Schafroth predicted it would, but doesn’t become a critical debate either. Barnes and Stillman, representing opposing sides, are equally manipulative, univocal and bureaucratic in the struggle for the interpretation of art, while Valparaíso doesn’t want to complicate her life with ideas about aesthetics. They discuss Juvenal’s interests and influences: Was his art political? Was his work minimal? Did he care about the public’s perspective? Did he like hanging out with art students? In reality, the panelists’ arguments are not really about Merst’s work but instead about themselves, their memories and perceptions of Juvenal’s motivations, intentions and energy, so it’s not surprising that the panel drifts into a sort of improvised psychodrama, a staging of anger, fears, resentment and frustration. It’s very meaningful that the projector doesn’t work properly so the audience is never allowed to see the work that is being discussed. Ironically, the panelists focus their attention on the pieces that cannot be shown rather than Merst’s works displayed around them. This is not only a curious Beckettian wink but also an intelligent comment on the immateriality of conceptual art. Barnes is an opportunist and self-promoter who can’t resist the temptation I never understood why people have such grandiose aspirations for what art can do. I’ve seen careers come and go, young curators turn into bitter critics, promising artists turn into cranky aged people.Why can’t we just take it for face value?...Why not be honest? Honest that nothing really changes, that nothing is radical…. We want art to be about the world, but in the end it is just a little lie, and that’s fine with me. This is just art. It’s always just art. In a way, the panelists are has-beens, or at least people who have lost their edge, people in transition, searching for themselves after having failed at doing something else. Schafroth says sourly: “And now here we are, wanting to make that past better than it was. Maybe because our present sucks so much…. As if we were refusing to accept that our lives were a thread of endless hopefulness and expectations.” So it is particularly ironic that they have gathered to celebrate the life of a dead man who believed that his art would live after his death, as Helguera puts it: “Merst was keenly interested in making his work highly visible in the long term and influencing the perception of his historical place in art.” We could easily think that Helguera is just having fun at the expense of some of the art world’s most common clichés. Nevertheless, his characters are far from being simple caricatures and their relations to Merst and his work are problematic, to say the least. The Juvenal Players is much more ambitious than a well-crafted and ingenious in-joke; it is, in fact, a brilliant perception on the nature of art, the artist and a creative process in which the artwork seems to fade into discourse, into a “cluster of forms of practice in which objects are mapped or proposed or prescribed,” according to art historian and critic Charles Harrison.i Helguera is not only interested in Juvenal as a symbolic and controversial figure, an amalgam that represents common contemporary strategies of creation and engagement with galleries, collectors and critics, but also as the idea of an artist who dematerializes along with his artwork. This is clearly not an art essay, but a smart reflection on the notion of ideas as art objects, a fable about conceptual art. The Juvenal Players evokes and establishes an interesting counterpoint to The Unknown Masterpiece, Balzac’s renowned novella. In this celebrated fable about modern art, the elderly painter, Freinhof, is obsessed with his art to the point of losing a sense of reality. While for Balzac the aim of art was “not to copy nature, but to express it,” for Juvenal, art is, as Sol Le Witt proposed, “made to engage the mind of the viewer rather than his eye or emotions.” Freinhof becomes blind to life because of art, “Art hurts you when you desire it so much,” writes Balzac. Meanwhile in Helguera’s piece, “The truth is unimportant,” as Schafroth states, and “Merst wasn’t interested in anything too much, he was interested in being uninterested in things,” as Miranda explains. Merst is described by his friends, lovers, colleagues and collector as a plagiarist, a conspirator, a prankster and a manipulative liar. But curiously that doesn’t make him less of an artist; on the contrary, for some, he is the ultimate conceptual artist. Pablo Helguera is also a splendid liar, a first-class storyteller, a curious mind constantly in search of stories, a creator of parallel universes and impossible characters living in credible situations, which invariably probe our certainties, intuition and knowledge. Helguera loves weaving intricate narrative tapestries in which reality and fantasy become entangled and the spectator has to deal with ambiguities in order to situate himself in relation to them. Helguera is not interested in puzzles but in exploring re-imagined realities, as in his book, The Witches of Tepoztlán, a collection of essays about four non-existent operas and their fantastic composers. Helguera’s work deals with memory, community, nostalgia and loss; he has taken on popular culture (by exploring phenomena such as Latin American Telenovelas or soap operas) and the extinction of languages and cultures (Eyak from North America), he is interested in social themes and lofty ideals (The School of Panamerican Unrest project, a multimedia experiment and a participatory piece in collaboration with a wide variety of art institutions, artists, curators, critics from all over the continent). Helguera “You all will be the players of my own life, the narrators of my story, and to you I entrust it. I wish I was there to see my life be told,” penned Juvenal in his testament of sorts. In many ways, Merst is a self-made myth, an artist who sculpted his own persona, he is the central piece in his oeuvre and Helguera demonstrates his impact on his circle of acquaintances as if he were sort of a human black hole, a charismatic individual capable of affecting everyone around him and transforming the lives of anyone who cared about him. As the conversation goes on, we realize that there is no way to talk about his work without getting personal. Juvenal was endearing and repulsive, fascinating and unnerving, a fraud or a genius capable of devastating spurs of sincerity and a frightening potential for disappointing everyone. Juvenal was able to bring out the best and the worst in people. One of the scenes of Merst’s film, Work Number 1 (1990) his first important and recognized piece, takes place in an Ames room where the characters move around. An Ames room is a stage that from the front appears to be cube-shaped but whose true shape is trapezoidal. One side is shorter than the other and the ceiling and floor can be inclined. This ingenious device creates an optical illusion by distorting the proportions of the objects situated inside the room. Helguera has created a narrative Ames room, a space of illusion where the proportion of his fictional characters constantly change, making them gigantic or minuscule with respect to the deceased artist. Instead of using a traditional three-dimensional Ames room, Helguera’s is multidimensional. In this peculiar and distorted stage, time, space, myths, emotions, art interpretations and a voracious search for meaning create an intimate (slanted, idiosyncratic, devoted and corrosive) portrait of that revered and wonderful freak show that we know as the art world. Naief Yehya

|

|