George Woodman

The Camera Obscura Photographs

March 26 - May 8, 2004

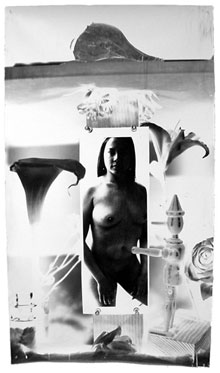

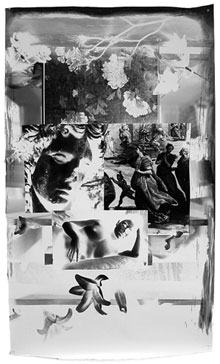

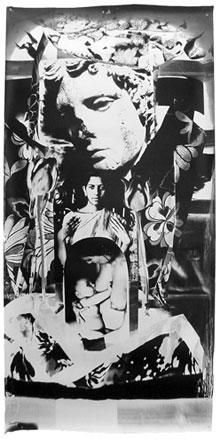

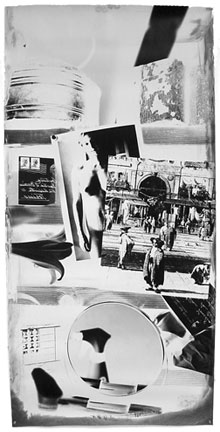

The camera obscura, first instrument of verisimilitude, is in George Woodman's hands an implement of deepest dreaminess. Working with a process of his own invention, Woodman creates big black and white photographs that are part photocollage, part shadow play, and part art history lecture as narrated by a lyric poet. The photographs begin with the composition of a still life involving objects and images, usually including Woodman's own photographs, often of other art. The arrangement is set up in front of the lens of a camera obscura built inside the studio. Within the camera (which is, of course, just a lightless room with a small hole in one wall, fitted with a lens), a big sheet of photographic paper is fastened to an easel. When the shutter is open, the still life registers on the paper as an inverted negative image. Woodman develops the print in the camera, applying the chemicals with sponges. Sometimes he includes negative images in the still lifes, which revert to positive when re-photographed. Long exposures - generally eight to ten minutes - allow objects to be moved while being photographed, creating transparencies and ghosts. The interchanges between positive and negative, art and its double, first, second and third orders of experience, and - perhaps most to the point - frailty and immortality are the murmurous heartbeat of this work.

In one photograph, a negative image of a manikin (from Museo del Costume, Palazzo Pitti), seen from the back and displaying an early 19th-century dress of great delicacy, is juxtaposed with a positive image of a real, contemporary woman in a sequined shift, seen from the front. Both are cropped at the knees and shoulders, hence immobilized and sightless. The mismatched images of the two women, facing each other (and us) across more than a century, form a metaphorical figure of dazzling complexity. The reflective quality of the sequins, as aggressively enticing as the fragile antique dress is modestly alluring; the melting grace of the floral border; and, not least, the paradoxical composition, in which the primary figures are both side-by-side (in the image) and face-to-face (following the logic of their relative positions), all augment the symbolic complications. As Max Kozloff has written of the fluid disjunctions Woodman favors, "A body is in two places at once, or causes uncertainty about its being anywhere at all, other than in the mind." Other features of Woodman's current practice help shape the work's meaning. The camera obscura, as he uses it, produces a very shallow depth of field, and the still life subjects are often similarly constricted. Taped to sheets of glass, or pinned to wooden boards, or held in place with string or rubber bands, or arranged on shallow ledges, the imagery's constituent parts, as photographed, seem to slip just forward and behind the image surface. The prints, moreover, are themselves often sufficiently large and rough around the edges (Woodman prefers to show them untrimmed and unframed) that they achieve a kind of independent physical presence, counteracting the refinement of the imagery with considerable material toughness. Woodman arrived at photography after thirty years of painting, nearly all of it abstract and much of it structured in such a way that he came to be identified with the Pattern and Decoration painters of the 1970s and '80s. He also acknowledges an affinity with such 19th-Century American realists as John Peto, whose trompe l'oeil still life paintings often share the spatial restrictions of Woodman's images. "A lifetime as a painter has left me comfortable composing things in a very shallow space," Woodman says.

The photographs made with conventional equipment that preceded Woodman's work with the camera obscura were closer to his paintings in their relatively tight, fixed structures. While that degree of control clearly appeals to Woodman, serendipity is a favored aspect of the current work; because the camera obscura has no viewfinder, he doesn't know what he's got until the print is developed. Paradoxically, one of the surprises of these images is their preternatural clarity. Big photographs are currently much in vogue, so viewers are accustomed to their logic: whatever their technical accomplishment, they generally lose resolution the closer the viewer gets. Woodman's big photographs, by contrast, are made without negatives and in consequence have no grain, so increasing proximity yields progressive levels of detail. Since the distance of the still life objects from the camera's lens determines their apparent size, some objects, including many of the flowers that appear in abundance, become greatly enlarged in the final prints. In these instances, the level of detail seems unearthly, and the more confoundingly spectral for being in the negative. On the other hand, where photographs have been re-photographed, graininess is sometimes exaggerated. And some of the subject photos were taken or printed to be exceedingly blurry in the first place, all of which only enhances the comparative brilliance and delicacy of those details taken directly from life.

Relative degrees of clarity also become increments of meaning. For instance, in The Rape of Europa, the rubber bands and thread holding the still life material in place are razor sharp, each frayed strand of thread clearly visible. The sculpture that is the re-photographed image's subject is clear, if a bit grainy, and a cameo portrait of a woman wearing a lace mantilla is fairly crisp. But there is a third woman, who alone seems to reside in the modern world. She is very blurry, as if thrusting herself forward into our time and place - too close to resolve, too familiar for us to see her clearly. Most of Woodman's camera obscura photographs are oriented vertically, but this is a horizontal composition, in which such violations of spatial protocol seem the more pronounced. "The vertical format allows for more graceful recession in space," Woodman says. "Horizontals are more aggressive." Sometimes, spatial aggression is indistinguishable from grace, as when a female dancer pushes away from the camera with one arm, which becomes blurred and radically foreshortened, the vigorous, even violent act producing a gesture that seems elegant as a bird's wing.

For all the refinements of Woodman's photography, he is not afraid of big, even ungainly subjects, among them eros and thanatos, art and nature, and the brevity of both. Sometimes there is humor, as when a suit of medieval armor is juxtaposed with a yielding naked woman, and again when a beautiful face is matched with the head of Medusa. A virile marble Jupiter holds an infant Dionysus as a man holds a baby, with reverence but impatiently, the image framed - hence, perhaps, further challenged - by a field of colossal, ethereal flowers. Often, voluptuous bodies are cut off at neck and thigh: static and blind, they are not less, nor more, than delectable. It can be argued that these bodies are thereby objectified, though of course they are often (sculptural) objects to begin with; by the same token, it can be said that the re-photographed art is, reciprocally, animated.

Woodman's own remarks about second-order art are oblique; his original imagery and its historical components tend, he says, "to coalesce into a new entity, not a 'sight,' but a 'seen sight' in which the strands of two different cultures of representation lie across each other, as in looking through air into water, then at the bent stick in the water, then at the pebbles at the bottom of the brook…." Having trained (at Harvard, under I. A. Richards) as a philosopher, Woodman is perfectly able (and liable) to put this perceptual conundrum in academic terms. But more salient references come from the world of poetry, literary and visual. The surrealist sensibility, with its inclination toward dreamlike conjunctions and displacements of existing objects and pictures, is surely relevant; Max Ernst's collaged graphic novel of polymorphous Victoriana, La Femmes 100 têtes, and Joseph Cornell's boxed assemblages, both seem pertinent. So, by Woodman's own account, is the melancholy, early morning Paris immortalized by Eugene Atget. Alain Resnais' filmic vision of the mournful seductions of Marienbad, as guided by Alain Robbe-Grillet's laconic screenplay, seems related too. Inevitably, comparisons will be made to other contemporary artists using the camera obscura, with Abelardo Morell's lush, richly layered interiors the nearest in spirit. But (as has been previously noted), of all Woodman's artistic kin there is none with whom he is closer than Francesca Woodman, the increasingly celebrated photographer who was his daughter, and who died, at 22, in 1981.

In art, George Woodman's particularly, time moves in more directions than one. Sometimes, briefly, it can be forced to stand still, but Woodman's focus is on the costs of the effort rather than its fleeting achievement. In a delightful series of mediations on temporality, Alan Lightman recommends that we "suppose that time is not a quantity but a quality, like the luminescence of the night above the trees just when a rising moon has touched the treeline." Under such conditions, "Time exists, but it cannot be measured" - conditions that prevail, it could be said, in Woodman's world. And if, as Roland Barthes says, the first cameras were "clocks for seeing," the units recorded in Woodman's current work conform to a temporal order all their own.

Nancy Princenthal

New York

2004

1 Max Kozloff, "Shades of Sculpture," Museum Pieces: Photographs by George Woodman (Lo Specchio D'Arte, New York, 1996), p. 12.

2 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (Hill and Wang, New York, 1981), p. 15.

Back to top

|

|