|

|

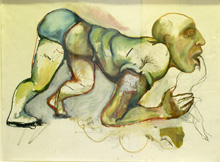

China Marks "I suspect myself to be half P.T. Barnum and half Jane Goodall." No ordinary self-description that, spoken by no ordinary artist. P.T. Barnum might disclaim paternity, but his showmanship still flows in China Mark's arteries. No element more pervades her work than drama. Seldom do her works depict a solitary object; more often they show two, three, or more characters in open conflict or in compromising situations. Untitled #7 exemplifies the imbroglios into which the relationships often knot themselves; one figure thinks of another who reflects on a cross, while holding on her lap a third figure, who watches a costume puppet animated by a fourth figure, from whose mouth a head emerges. No one figure focuses attention; the viewer's eye must wander from figure to figure in an attempt to incorporate it all. A different drama animates Riders to an Inland Sea, which foregrounds four figures, two riding, two being ridden: as in many of China Mark's works, the interrelationships between the depicted subjects do not exhaust the interrelationships engendered by the drawing. One ridden figure looks down to hell, the other up to heaven, but both riders look out from the picture plane, invoking the and rendering complicit the viewer. Even when only one character appears, it manifests the schizophrenic split inherent in humans, the split Plato called the tripartite soul, Freud designated as id/ego/superego, and Theodore Rothke celebrated in song : "We are one, yet we are more,/ I am told by those who know,- / At times content to be two." In Portrait of the Artist as a Moral Idiot, for example, the central figure grasps and ingests or expectorates a shadow self, and in Untitled (#9), the unity or separation between the two figures remains ambiguous: do they make one person or two? The drama of multiplicity appears in other ways as well. Mark's protagonists mimic Proteus, by perpetually mutating, morphing from one creature into another. These works show us dog-boys and bird girls, devil- people and dinosaur-people. No identity remains fixed, although ( true to Einstein's law) what China Marks's world sacrifices in stability it makes up for in energy. If her Barnumesque dramaturgy barks to all bystanders, Marks's consanguinity with Jane Goodall announces itself more subtly, in her commitment to the accuracy of observation that Wallace Stevens calls " the equivalent of accuracy of thinking." The subtlety lies in distortion. Poets and novelists try to tell the truth, but they do so precisely by lying; visual artists try to depict one reality by creating another. China Marks creates not a Borgesian map that is the territory, but a map that maps our world by being a world parallel to our own. She sees our world by seeing something else, as have all mystics and visionaries. All the efforts of the Hebrew Patriarchs and Euroamerican Protestants to construct an aniconic god fall away beside the sixteen -square foot affirmation of idolatry China Marks calls Bird Girl gets Sanctified. Moses may have seen no more than God's backside, but Bird Girl looks into His eyes. Martin Luther may not have seen God, but China Marks has. Its genealogical accuracy aside, Mark's Barnum /Goodall self description also names her androgynous artistic nature. Not epicene void of sexual characteristics but sexually overdetermined, celebrating all sexual possibility, polymorphously perverse. China Marks sings with Walt Whitman, " I will show of male and female that is but equal of the other./ And sexual organs and acts! Do you concentrate in me, for I am determin'd to tell you with courageous clear voice to prove you illustrious." Some of the works wear their sexuality on their sleeves, as in the finger-fucking in Untitled (#12), but at least as many make their sexuality more ambiguous or implicit. Is there a hint of anal intercourse in Riders to an Inland Sea or more than a hint? Is the bondage there sexual? As in Freud, so in these paintings and drawings every part of the body becomes an erotogenic zone, and every object a sexual object. China Marks describes the "parallel world" depicted in her work as "primarily an oral society." Oral, I would add , in more ways than one, and in no way more obvious than in the mouths of its denizens. Many mouths, voracious mouths. China Marks's work portrays a labial parallel world, from earlier sculptures like Loss and The Player and the Played through these recent paintings like Prisoner of Childhood. Those Whom the Gods Love she tells us in title and drawing alike,They Eat Slowly. In the sculptures with which China Marks began and matured her artistic vision, in pieces like Domestic Drama and Trio with Spoon, the characters eat each other politely, with utensils, but in her current work, the characters, now ravenous, eat each other whole. In addition to the morality of mouths and tableware, the orality of these words marks these works. Any land speaks a language, and China Marks portrays a polyglot parallel world but her titles reveal at least one of the languages as our own. Many of her titles use jokes, puns, allusions or double entendres. In Baby Buggy, for example, the word " buggy " means infested with bugs ( as the baby becomes when its two legs are added to the highchair's four), and crazy ( as who wouldn't be in such a household), besides calling to mind the tongue twister "rubber baby buggy bumpers." Similarly, the title Flesh Wounds ( like the drawing it names) might be read with flesh and an adjective modifying the noun "wounds", or with "flesh" as the noun and "wounds" as a verb. Words occasionally bubble to the surface in the works, as in Hope and Despair Greet the New Century, where enigmatic phrases ("Awkward as a young girl at her first dance...") mix with aphorisms ("Of course, to despair is to deny our children their future..."). More persistently, though, these works speak a visual language, in which the recurring elements, from animal parts to bones to ropes and chains to enclosures, create a code that makes Marks' corpus the score of the humming you will hear in you head when you close your eyes tonight. In addition to the artist's self-description one might find other flints to strike against these works, for they are hard and give off sparks. Look to Lear; that bleak world, that nihilo from which we are not exed, the character who sees most clearly is the fool. As in Lear's world so in ours, where death no less inevitably ends all: " if the fool" ( Blake says) " would become wise." In Lear, that most tragic tragedy, wisdom nests in the comic. So too in China Marks' works. No less portentous than Lear, these paintings and drawings are no less frequently funny. Look at the serviced woman's expression in Room Service, or imagine, how a child might react to Untitled (#7). Fools can disarm us long enough raise questions we might not ask otherwise. What does a fool in stripped pants know of the devil ? Is there a circus on Mars? If Greek sculpture perfected the representation of three dimensions in three dimensions, and Renaissance perspective perfected the representation of the three dimensions in two dimensions, then twentieth-century visual artists ( like their contemporaries in physics and psychology and poetry) work under the obligation to represent more dimensions than three. Physicists now speak of twenty and more, and artists too must synthesize/ synesthetize more dimensions than length, breadth, and depth. China Marks aspires to such a synthesis. Her mixtures of media lend complexity to individual works and the oeuvre; her imbrications of pattern and figure and the consequent interpenetrations of perspective and flatness force the eye to find its own way though each piece; her titles infuse another medium, spoken language, into the work; her teratological figures invoke mythology and dreams. These works speak to our sexual selves, our religious selves, our contemplative selves, and our primitive reptilian selves. Their rich entanglements culminate in A Grown Woman, the most recent piece in the show, by becoming the liana depicted there. Profuse and lush, they grow around us and take our own shapes, becoming a polydimensional cast that will stand after our passing. These works compress whole histories into themselves: simultaneously etiologically and eschatological, they embody the identity of an end and beginning T.S. Elliot nods to in Four Quartets. Not only in the ubiquitous sexual birth/deaths of their subjects and in the messages each medium channels into the whole do these works show us our end in our beginning, but also as art, which can become its own future only by representing its past. Knowledge grants gravidity, and China Marks knows all the art she can bear. Sometimes her re-presentation announces itself, as in The Temptation of St. Anthony and the fools that recall Picasso's harlequins , but more often it works tactically, as in Room Service, where the entangled lovers and their pet cannot but call to mind Leonard's Virgin and St. Anne, their legs emerging from beneath their drapes, the impish boy by nearby. The temporal compression of China Marks's works insists that this meditation end as it began, with the artists own words: these drawings and paintings create for the viewer " a stroll, a scramble, a trek, a climb through a vast terra incognita full of wonderful plants and animals and ravishing vistas at every turn." H.L. Hix

|