|

|

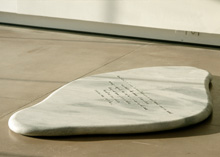

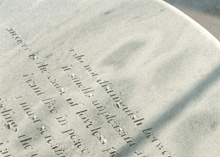

Hirokazu Fukawa I receive crazy orders sour as vinegar from the heart of the strange internal festering command center responsible. Once in a while, during the course of an everyday activity, we may encounter an incredible moment of truth. However, this moment may be too profound to keep in our mind because our daily activity overtakes our attention, and we either forget about the moment or put it deep inside our brain cells where it resides without ever having been verbalized....Art then can become a vehicle to rescue this profound thought from thought form the deepest recesses of our memory. My installation[s] ...[are] intended to function like an entrance way for this rescue mission.Since 1992, Fukawa's work has become increasingly conceptual. In an installation titled I Want to Feel the Way You Do All the Time... the artist gathered 210 salted fish which he individually mounted on steel stands and placed in two concentric semicircles facing a line of video monitors. The smell of preserved fish, common in Japan but considered noxious in the West, permeated the gallery, adding another sensory level to the viewers experience of the installation. A line of video monitors, five to a side, bisected the gallery space, the majority offering only minimal visual data: four views of ocean horizons faced the saltwater fish, four river horizons faced the smaller, freshwater fish. By contrast, the fifth monitor on each perimeter continuously showed CNN's Headline News providing a glut of information. Participants waded through the installation, as though walking on the ocean floor, with the fish placed at knee height and the video screens reflecting a blue hue. During the summer of 1994, Fukawa was invited to create a installation at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. Titled Love Me in Your Full Being, the work consisted of two rooms, one hexagonal, the other forty-eight feet long by fifteen feet wide. The artist propped up huge mirrors along of the first room, creating endless, polygonal space. On each of the mirrors, Fukawa sandblasted texts which are self-explanatory but subtle and ambiguous. In the middle of the room, he placed steel rods embossed with passages of William Blake's poem Song of Innocence. At the entry to the second room, Fukawa arranged a large screen onto which he projected images of sea turtles swimming underwater and flames of burning dictionaries. Beyond the screen, an iron staircase with glass treads filled the room. Sandblasted on the top step was a statement by Soviet astronaut Aleski Lenov: "It was a great silence, unlike any I have encountered on Earth, so vast and deep that I began to hear my own body." In describing this installation Fukawa noted, "The texts are neither political cautions nor educational messages. However the pieces will become devices for looking at ourselves, and our society at a deeper level, introspectively." The current installation, Like an Ethereal Transfer, synthesizes elements of Fukawa's prior work in a haunting and evocative manner, that continues his fascination with communication. Exploring restricted transfers of information, several years ago the artist became interested in autism, a state in which individuals are trapped in their own minds, often unable to communicate with the outside world. Fukawa's son, Fumi, is autistic, and as the artist conducted research, he found that the majority of books written on the subject viewed autism from the outside, as distanced observation. In time, Fukawa discovered the writings of Birger Sellin, an autistic whose only means of communication is the written word. In Sellin's writing, one can sense the frustration of a trapped intelligence with little means of ever engaging another human in dialogue: an annoying thing I know my way around so well inside my own world but reality is different in a scary way... our world is inaccessible and sad i want to point out that i love my own reality too it offers me protection and refuge it gives me dignity no one despises me there because i am recognized there an opponent of realityIn his most recent work, Fukawa incorporates several of Sellin's writings, sandblasting phrases onto the smoothed marble surface of irregularly shaped stones. The artist then fills the gouged areas with mercury, a viscous, poisonous material that slips away and balls up into increasingly tiny spheres, resisting attempts to capture or contain it. The phrases Fukawa chooses to include reflect Sellin's outside world as experienced from within his own mind: i do not distinguish between their anxiety and mine it smells unpleasant and transfers itself to me anxiety is the cause of love loves people the cause of harshness and terror i can't live in peace and quiet with this anxiety i must scream anxiety gives the boxed in feeling the upper hand and they stifle me i am without me i am a slave to the vast force of anxietyIn another section of Like an Ethereal Transfer, Fukawa constructed a marble bed with large hole situated at its head. The bed is based on a similar one in the psychiatric hospital museum in St. Joseph, Missouri, part of a display exploring how ignorance of various conditions, such as autism, has traditionally resulted in hospitalization of people whose differences lies not in a lack of awareness or intelligence, but in their inability to communicate in a communally accepted form. On the smooth surface of the bed, the artist arranged a cue ball and a set of numbered pool balls, reflecting many autistics' love of repetitive activity. Using a 1,000 watt spotlight, Fukawa projects Fumi's silhouette on the wall, not in shadow but in light. Despite the specificity of this image, the installation is reflective of all humans, so often trapped within ourselves, unable to communicate or even access our deepest thoughts. The work is a fitting metaphor for Fukawa's thinking on the function of art: Most people experience life through everyday activities rather than through philosophical contemplation. Art helps us connect.... with things which are concrete but cannot be communicated well through language. Only art can communicate these connections...allowing us to experience a typical activity in a new, mysterious way... Barbara Bloemink

|